It’s not easy to become a top lawyer, or everyone would do it – but how hard is it really to make your mark in the legal industry? We’ve crunched the numbers so that you don’t have to…

Michael Bird, January 2020

Whether you’re aiming to join the ranks of solicitors at a top firm, or it’s the Bar and nothing but the Bar for you, becoming a lawyer is not going to be easy. Just getting the necessary qualifications – degree, GDL, LPC, BPTC etc. – takes years of hard work and a fair bit of cash, and that’s only part one of the challenge. You’re not the only one making this journey and everyone’s gunning for the same end goal. You might already be dreaming of a plum job as a partner at a top City firm, for example; there’s a loooong way to go before you have a chance of getting that far, and the hardest step might be the first one: getting a training contract.

The stats make for more depressing reading than the 45th President's Twitter feed. Somewhere between 5,000 and 6,000 students complete the LPC each year; while there's a similar number of training contracts on offer annually, that wasn’t the case immediately after the 2008 financial crash and there’s now a big backlog of applicants looking for training contract spots. If you crunch the numbers from the last few years of qualification rounds, you’ll discover there are potentially over 10,000 people still searching for training contracts. Wannabe barristers have it even harder: fewer than 500 pupillages are on offer in a typical year compared to 3,000 or so annual applicants. Yikes.

Room for one more?

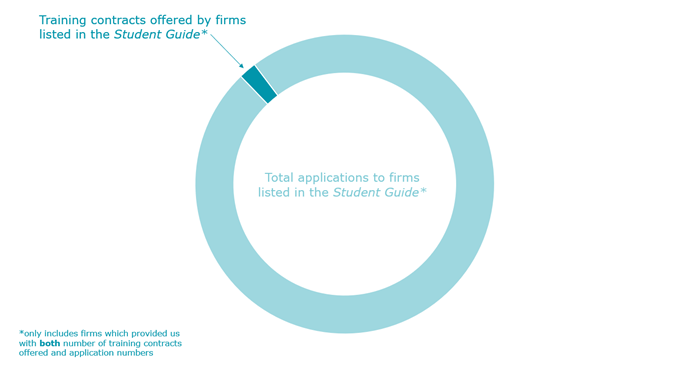

Let’s go deeper, starting with training contract spots. Below is a graphic comparing the number of training contracts offered each year by 82 firms listed in Chambers Student Guide’s 2020 edition, to the number of applicants those same firms receive.

Altogether these firms were offering 1,357 training contracts per year – and receiving a total of more than 70,000 applications. That translates to a 2% success rate. Of course, some candidates probably applied to more than one of the firms included here and so the proportion of successful candidates would be slightly larger than indicated, but it’s clear that competition for training contracts is extremely fierce.

We broke down the data further and explored how success rates differed between different types of firm. Some types are more popular than others – overall, firms based in London receive more applications than regional outfits even if they don’t necessarily offer more training contract spots.

With 7,310 applications for 184 training contracts, regional firms were the best bet for success according to our research, though at 2.5% that’s still very long odds. You may have predicted that elite US firms in London – famously home to small trainee intakes – would be the most competitive, but they're edged out by non-City London firms. Just 1.15% of applications to these firms (including Boodle Hatfield, Bristows, Mishcon de Reya, Russell-Cooke and Withers) scored a training contract. Like their US counterparts these firms favour small intakes; but the stereotype of long hours at American firms may put some candidates off from applying, a problem not shared by homegrown London outfits.

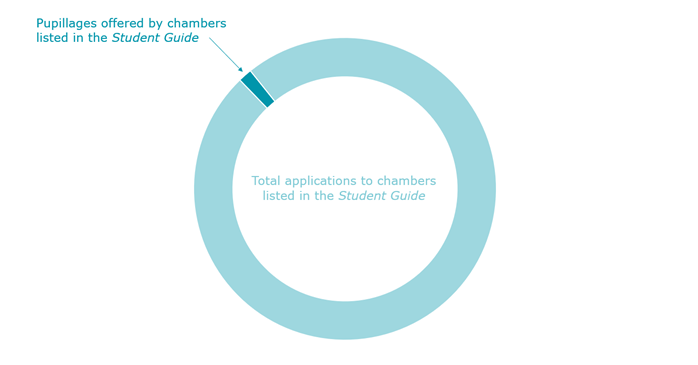

If you think prospective solicitors have it hard, wait until you see the stats for the Bar. Becoming a barrister is that much more difficult because the number of pupillages offered each year is much lower. When we speak to the lawyers of the future at careers fairs up and down the country, approximately half tell us they want to go into the Bar; many likely change their minds once they realise just how oversubscribed this area of the profession is, but even once a certain number have become disillusioned there are still far more candidates for pupillages than there are spots available.

While training contract applications had a 2% success rate in our survey, chambers were even more difficult to break into: only 1.5% of applications for pupillage were successful. The number of pupillages offered by sets listed in Chambers Student was 92 in our 2020 edition; those sets received a total of more than 6,000 applications that year. Again, we take this with a pinch of salt as most candidates will have applied to more than one chambers and we can’t account for this; but the overwhelming image is of too many people, not enough opportunities.

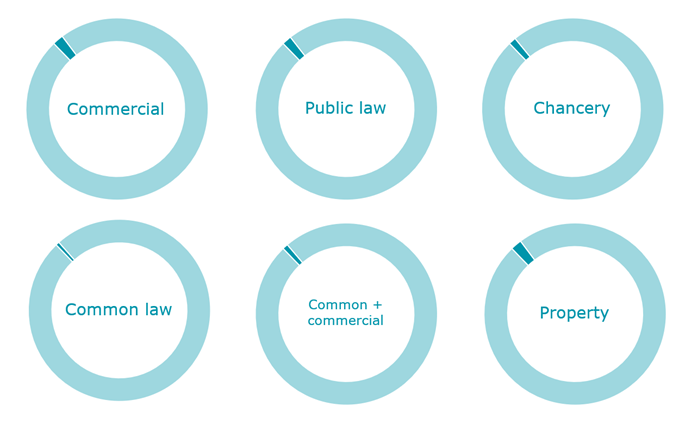

To round this analysis off, we categorised the sets in our survey by the type of work they primarily do, to find out which areas of the law were easiest (and hardest) to break into.

With a spectacular (comparatively speaking) 2% success rate, property chambers are your best bet for success according to the results, though commercial runs it close and there are many more chambers doing broader commercial work. Bad news if you’re determined to become a common law specialist – the proportion of pupillages to applications is just 0.655%.

These images may make the odds look horrific, but don't let them deter you if you're totally committed. Every year there are thousands of applicants who prepare carefully for the process and score the training contract or pupillage that they’re looking for. All of them did thorough research before diving in and we’re willing to bet a massive chunk relied heavily on the True Picture, Chambers Reports and other resources offered by Chambers Student. Do your homework to find out what your dream firm is looking for and you’ll stand an much better chance of ending up in the happy end of these figures.

Dream a little bigger, darling

So that’s getting into the law at entry level – what about career progression once you’re in? How many of the trainees starting at firms with fresh faces and big dreams make it to the top of the mountain?

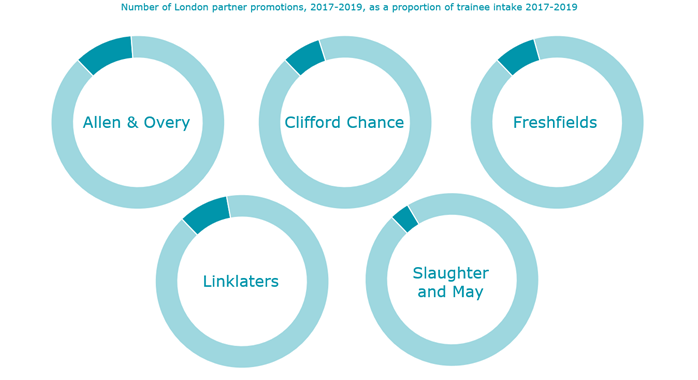

To get an idea of how many trainees at a firm are likely to make partner, we accumulated three years' worth of stats. For a series of firms, we totalled up how many trainees they recruited between 2017 and 2019; and how many partner promotions they made in the UK in that same three-year period. We didn’t count lateral partner recruits in this survey, only associates who’d been made up to partner within the firm.

We started with the old favourites of City law – the Magic Circle. Most had a similar proportion of partners made from their trainee intakes. The odd one out (as they are in many ways) is Slaughter and May, which recruited more than 200 trainees over three years but only made nine UK partners in that time. Allen & Overy was the ‘best’ performer: with 28 partner promotions to 227 trainees, that’s 12% of trainees making partner down the line. It’s not an exact comparison, of course, as the journey from trainee to partner will take eight years at an absolute minimum.

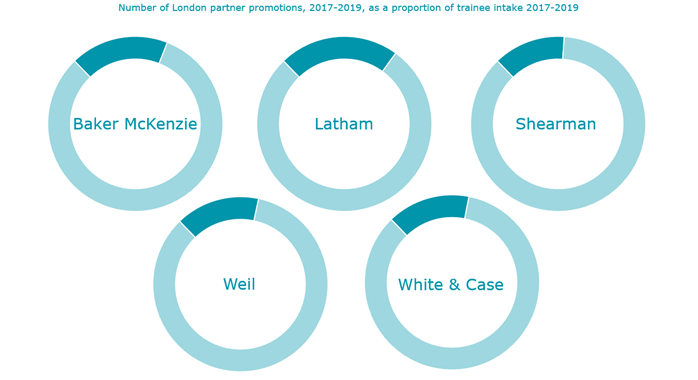

How does the traditional UK elite compare to its American competitors?

Just a glance will tell you that US firms make more partners compared to their trainee intakes. The five firms we selected made fewer internal promotions overall between 2017 and 2019 but recruited much smaller trainee intakes between them. We picked five US firms with sizable enough annual trainee classes (minimum 12) for meaningful data. Latham & Watkins was the ‘top performer’ from this cohort, with 16 UK partner promotions in the same time frame as 56 trainees hired. A 29% conversion rate clearly tops anything in the magic circle.

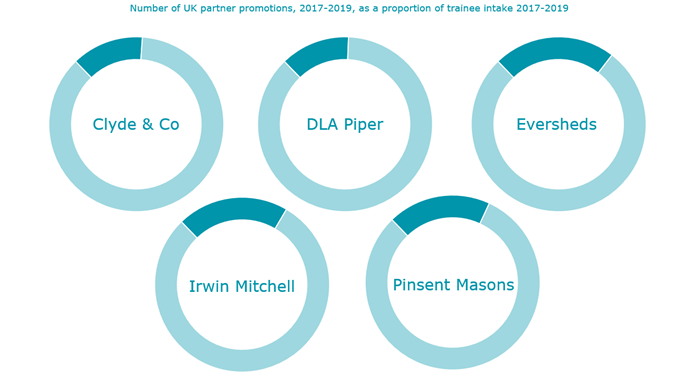

Not everyone wants to work in London, and we thought it was only right to include some national firms too. The five we selected have some of the largest headcounts in the UK; for all of them we took both national trainee numbers and nationwide partner promotions.

Matching Latham at 29%, Eversheds Sutherland is the best performer of the national outfits we surveyed; Irwin Mitchell and Pinsent Masons also top most of the other firms listed. Just as firms outside London have a higher ratio of training contracts offered to applications, national outfits are also the best bets for making partner down the line according to our results.

Where do all the trainees who don’t make partner go? Many will take (arguably) less demanding in-house positions at their firm’s clients, or legal roles in government organisations. Others will leave law altogether. A decent handful will jump ship to another firm at around senior associate level, many with the aim of making partner there. We hear time and again from senior lawyers that the old model of joining one firm and sticking with it until you make partner is less popular among millennials. Once you’ve earned a training contract and (hopefully) an NQ role, opportunities will appear that you didn’t know existed.

Think happy thoughts

We’ll say it again – don't let any of these statistics dishearten you. Heading into 2020 the legal industry may be more competitive than ever, but it’s also a very exciting time. New technologies are being invented that are redefining how law can be practiced, and young minds who can get to grips with those technologies will be essential for firms to survive and thrive. The political landscape is shifting in ways that seemingly nobody can predict – and uncertainty means work for lawyers.

Many applicants don’t land their training contract or pupillage of choice. But with a lot of hard work and a little bit of luck you'll soon discover that opportunities are everywhere if you look for them.

These stats make it very clear that if you want to become a lawyer, you need to prepare yourself as thoroughly as possible – and the place to start is the Chambers Student Guide.